Pennies and the Tour Eiffel

Looking through artifacts and being surprised, and not surprised, by who I once was

I haven’t had a haircut since April. At one point in my life, as a graduate student here in New York, this would have been a financial necessity based on a mistake I made only once. I had the choice of a $12 dollar haircut at Astor Place whenever I needed it or a $35 dollar haircut at a hipster place in Williamsburg twice a year. After my third Astor Place cut, I returned to school wearing a hat. When I took it off at happy hour with my roommates and friends, the entire table burst out laughing: the barber had cut my bangs straight across my forehead like a mother might do to a small child, holding a bowl over his head to keep the edge straight.

Like my mother did, I was reminded this week, to me as a child.

You see, I’m moving. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve taken more and more joy in being the opposite of a packrat. Throwing things out – jeans that fit but that I haven’t worn in three years because I don’t like how the denim feels, that lamp that I inherited from some ex or roommate that still works but is just ugly – has taken on a nearly holy or almost sexual satisfaction. I have one box, though, full or artifacts that go years without use but that I will never get rid of, the detritus of a life, one-of-a-kind accumulation from Washington State, from Minnesota where I went to college, from Grenoble, from life before everything was digital if it existed at all.

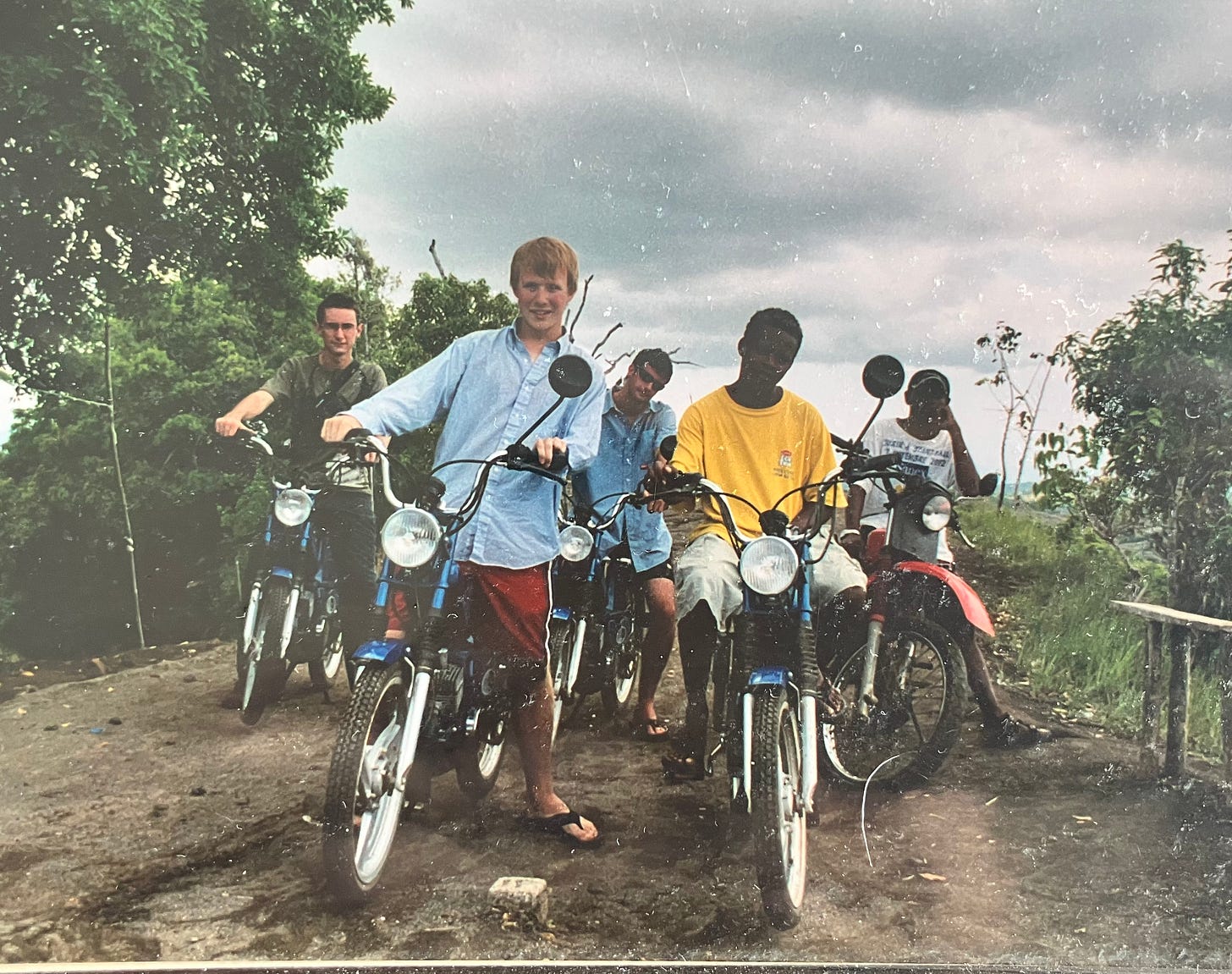

Middle school yearbooks. Film photographs. My high school writing portfolio. Polaroids of me with that ex-girlfriend. CDs of photos from my study abroad – 2003, Madagascar, with host family, with Lulu, on a hike, in a city.

I read Joan Didion’s Slouching Toward Bethlehem my freshman year of college on the advice of my next door dorm neighbor, Annie. It was one of the books who made me who I was becoming: Yes, a child of the rural west, a town where no one ever leaves and only the wrong things change. I was already, I see now, becoming who I am now: An East Coast Socialist Bisexual because even being gay was too normative. Exhausting.

“I think we are well-advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be, whether we find them attractive company or not,” Didion wrote in an essay on keeping a notebook. “Otherwise they turn up unannounced and surprise us, come hammering on the mind's door at 4 a.m. of a bad night and demand to know who deserted them, who betrayed them, who is going to make amends. We forget all too soon the things we thought we could never forget. We forget the loves and the betrayals alike, forget what we whispered and what we screamed, forget who we were.”

Every time I sift through this box, I find a few things I can discard. This time: the folder of information I received upon starting my PhD. It had no notes, nothing personalized, just a bunch of PDFs I could probably still find online.

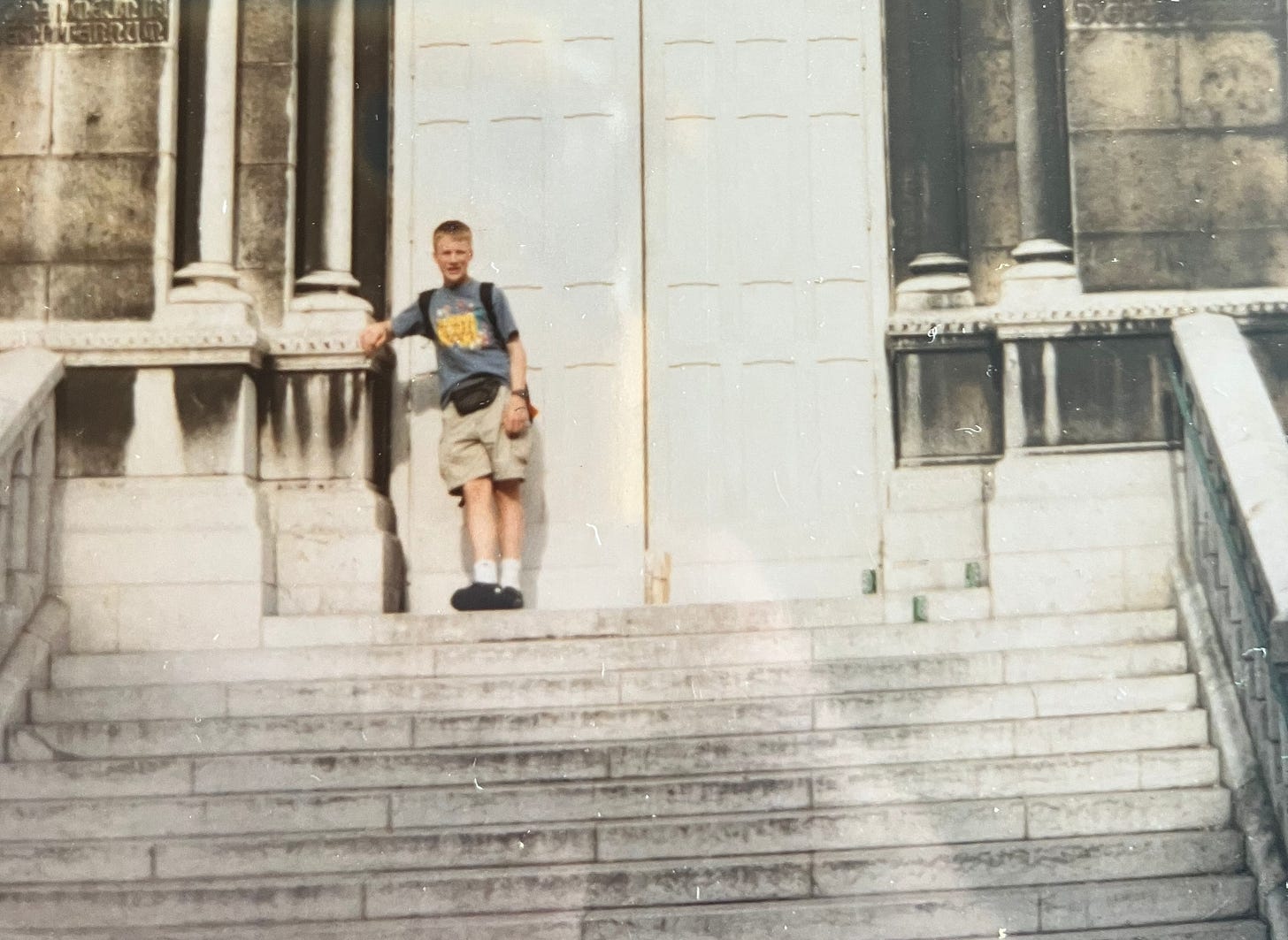

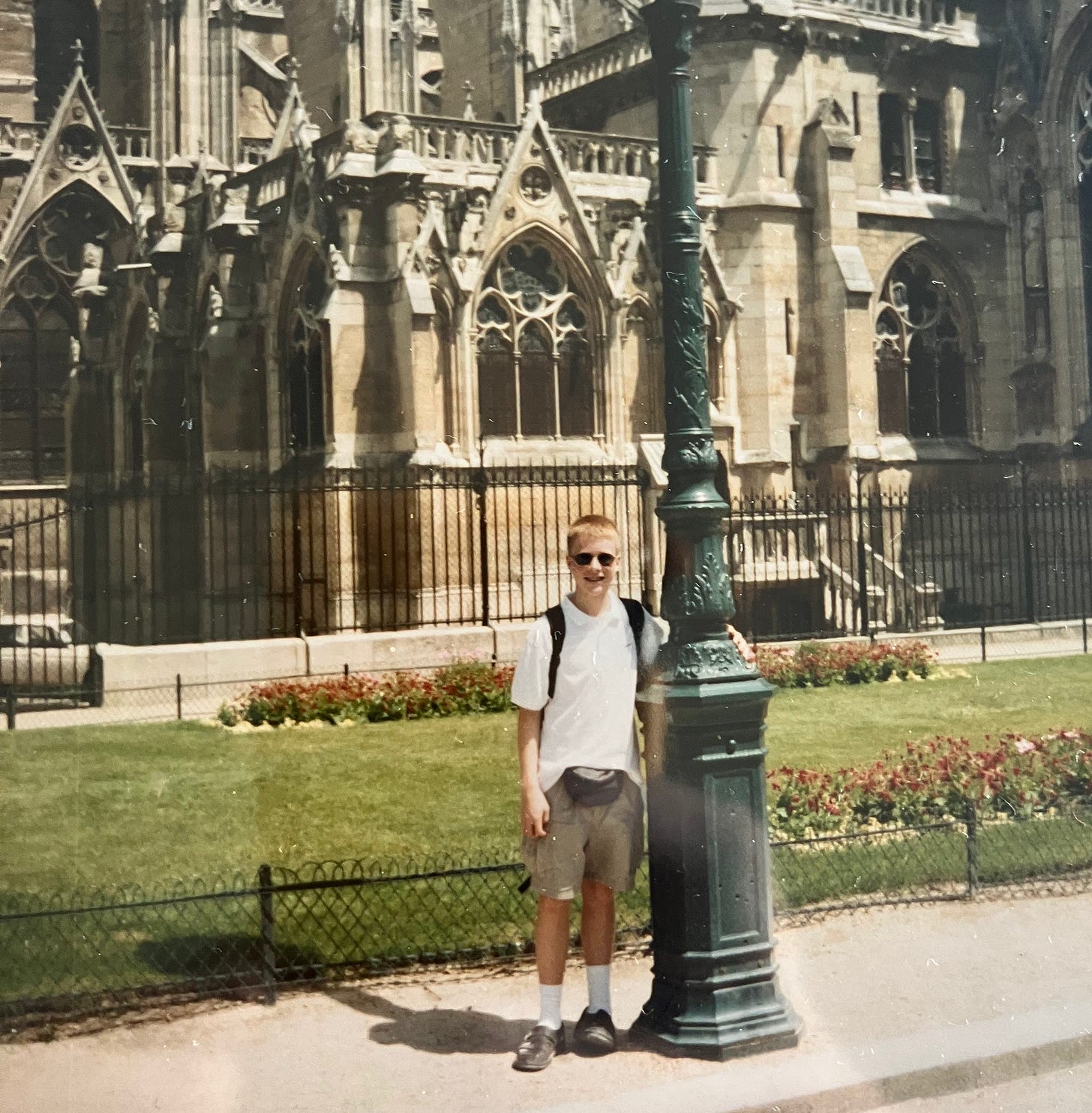

Every time I sift through this box, I find a few things I forgot to remember. This time: hand-written notes from the first few days of a 1998 trip to France. The context here: no one in my entire extended family had ever left the country. At 15, I was our first passport holder. Context: I fund raised by selling chocolate and magazine subscriptions no one wanted. I remember the cost of the trip exactly: $3200, an amount of money that seemed to me then impossible, is that what a house cost, or a car? It was a grownup amount of money, and I was still a child.

On the first day, we took the subway: “The métro system is very frustrating. It takes a long time to get from point A to point B.” Who was this child?

“The Eiffel Tour” I wrote, “is great, but there are too many people. The view was spectacular, but it was often obstructed by people.”

I was visited in Paris by Zofia, an exchange student from Belgium who had lived with my family in Washington for a year.

“With Zofia,” I wrote, “we went to the Parisien places. The spots where they just hung out in little cafés. We sat, eating fresh Strawberries, and watched the crowds. Everything was insane as we sat and watched. Cars, motorcycles, bicycles, and pedestrians scurried along as we savored the atmosphere. This is the best part of the day.”

“6/21/98: Inside Versailles,” I wrote, “is not that impressive…” I know what I meant: it was gaudy, over the top, a disgusting display of opulence that American culture had rightly trained me, via the aesthetics of people like Donald Trump, to despise out of class solidarity. “... but the gardens,” I continued, “are forever in mind.”

This child, so earnest, trying so hard to be refined, I recognize as myself. I recognize his petty annoyances, and what he found transcendent.

“Just remember the green, the water, and the people. The rest is unable to be shown on the page. Le jardin de Versailles est le plus beau jardin dans le monde.” Dans le monde. In the world, as if inside a globe. His imperfect French, just perfect.

I was raised Catholic, a past I have tried to forget. I wrote: “We saw Sacré-coeur, what a glorious sight. God touched the hands of the builder who did the work.”

I do not remember myself as a child who thought or wrote this way. Who is going to make amends? What would he think of me today? I didn’t even know I was a fag.

My version of the story is that, because I am and always was attracted to women, I came into my queerness late, recognizing crushes on boys in high school only in retrospect, after the possibility or need for action had passed.

I revisit this past self who believed in builders blessed by God not oppressed by man. I revisit this self because we are moving. I know him because of this box.

Here I am now: Devon and I helped clear his parents’ apartment in Queens, where he was raised and where they’d lived since 1994. Since 1994, his dad had collected pennies. Next to the pennies, a photo album of Devon, at 11, on his school trip to Sicily, with the town’s mayor, with his host family. Pennies. Pound and pounds: two metal boxes, four gallon ziplock bags, a navy blue canvas duffel. Two dollar coins, nine quarters, 106 dimes, 11 nickels, and 17,415 pennies. At 2.5 grams per penny, 1000 grams per kilogram, 2.2 pounds per kilogram: 96 pounds of pennies.

While Devon took care of some chores in the apartment, I loaded the pennies into our car. The first 8000 or so, I placed into a Coin Star machine in Jackson Heights alone: tedious work, it took some 50 minutes for them to clink into the machine as the numbers counted up on the digital screen. My time was running short, so I printed the receipt, and we returned together later to finish the task.

Devon and I loaded coins, then together, discussing with great seriousness the way to maximize the rate of counting: helping the coins into the slot with his fingers or lifting the gate to roll the coins in slowly. Answer: his fingers. We laughed together at the looks on the faces of strangers coming to the transfer point to send money to this country or that: What were these two people doing with so many pennies? We seemed to know as little about it as they did. One child stood two feet from us while his parents were in line as if we were a cartoon on YouTube, the strangeness of our duffel bag of change, of the synchronicity of our movements as I cupped handfuls of pennies into the machine and Devon fed them into the slot. Both our hands, over time, turned green-gray with the slime that coins accumulate. I pictured all of the hands, from before 1994, that might have touched these coins before they ended their lives here.

The Eiffel Tower: wrought iron. Pennies: zinc with a copper plating.

“This is so much better doing with another person,” I told Devon. “It was so boring here by myself.”

“It’s kind of fun,” he said, “but I wouldn’t want to do it alone.”

We had fun together. We went to Friends Tavern to wash our hands, and why not get a drink. After a drink, before I drove home, I insisted on food: spicy Chilaquiles from a spot by the subway.

I’ve moved, on average, every two years in this city. Packing and repacking the box that contains my past self. Throwing away a few things, keeping most. I hope I continue to be surprised, with each visit, by a new memory I find there that I didn’t know I had lost.

I remember the child I once was who went six months without a haircut because money was that tight. I am no longer that kid. I haven’t taught since May, and it has been a relief, in a way, to let my hair grow. Proof that I don’t have anyone to impress. This summer is about growing inside the home, being ready to move the home. It’s about writing and revising, personal work. Come fall, the clippers will be there. Come August, a friend is getting married, and I will be ready to step out of the house.

But next week, the movers come. We will land in Manhattan. In my box of artifacts, I found a letter I wrote, in 2001, to myself five years in the future. What did I imagine? School, a girlfriend, maybe wife, not-yet kids but soon, a degree in virology, a job as a scientist. Kids. “They will be on your mind,” I wrote at 18 to myself at 23. How much I knew, then, and how little. Kids on my mind. How much I love the child I once was, how curious I am about how his life will end up, and my own.

One of my favorite memories is us sitting in front of a big screen hanging from the Palais de Chaillot??? watching the World Cup soccer...pardon, le foot....while you cradled the ubiquitous soccer ball. I have no idea where all the others were she admits irresponsibly. Oh, and just to let you know: you growed up good.